“Imitation of Life?”

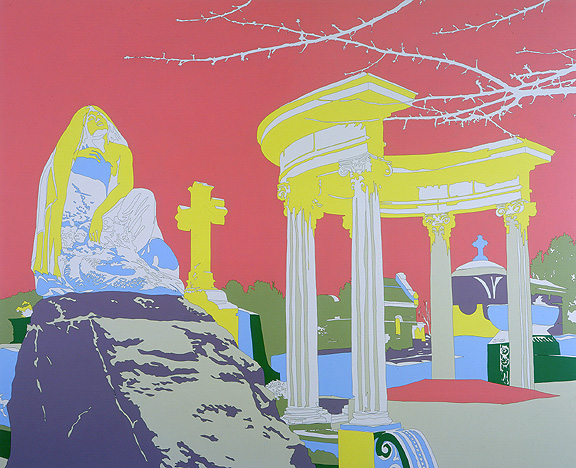

Well, what isn’t these days? Another resonant title in director Douglas Sirk’s parade of shackled emotions appeared the year before Imitation, his Hollywood swan song: A Time to Love and a Time to Die. What is helpful here is not the keystones of living and dying, though they are not completely irrelevant, but the intimation of an orderly, cyclical – if by no means “natural” – unfolding of human events, discretely rendered yet compressed in a bewildering veneer of loss; when are those times and how are they related? Clearly Lisa Ruyter’s paintings are steeped in time, slathered with an thick, allusive coating of temporal moments extending from the optical encounter between embodied viewer and painted surface to a wistful eternity limned by cemetery monuments to anonymous, plus a few decidedly less anonymous, victims of history. In her work, graphic as well as verbal traces of history, of personhood and place as verified by photography, collide with, merge into, and ultimately flaunt the all-or-nothing presumptions of ‘now’ and ‘forever.’ By the same token, half-remembered references to detritus of mass culture – the paintings’ cinematic titles for sure, but also certain objects or scenic arrangements within the work – conspire against the immediacy of vibrant color and rhythmic jounce of shape and line. Nonetheless, calibrated within the fabled push-pull of formal/representational tensions, Ruyter’s bows in the direction of symbolism or shared iconography, the last century’s twin edifices (crutches?) of social critique, neither overwhelm nor are totally subdued by uninhibited adventures in spatial and temporal mapping.

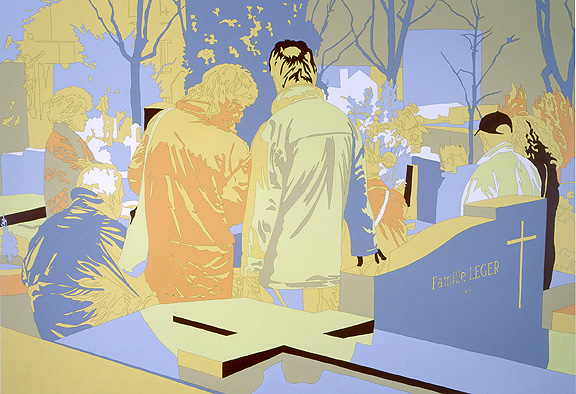

Of crucial import is the strong sense that her work is not concerned merely with images of images, with the philosophic impossibility of grasping any external reality except through increasingly debased, mechanically reproduced ‘imitations’ – a founding principle of Pop Art and its photo-obsessed offspring. Some residue of banal, quotidian realities trapped in premising snapshots hovers over Ruyter’s sumptuous transformations. An actual, experiential instant of inception is especially ripe in the seven figures gathered around Edith Piaf’s grave in “The Hole.” Who they are hardly matters. Moreover, they are frozen rather than momentarily stilled, as drained of potential mobility as statues or burial vaults. Their volumeless particularity is grounded less in indices of age, gender, class, or culture than in their newfound function as irregular screens occasioning the colorful imprint of light and shadow. Like store mannequins in “From Pole to Equator,” the planes and crimps of their clothing bear fleeting marks of a determinate time and place. Corporeal ‘testaments’ to the persistence of past lives, these figures mediate an eerie passage from semi-permanent slabs of stone to (even more) semi-permanent slabs of painted canvas.

Meanwhile, their considerably less articulated facial outlines, a conventional font of expressivity, direct our attention to an intervening stage in the transition from snapshot to finished object. Adopting a technique that borders on the para-cinematic, Ruyter projects a photographic slide of her subject onto a monochromatic canvas then in a single session traces the basic composition with a black marking pen. Akin to the method of ‘rotoscoping’ used by avant-garde film animators like Robert Breer, Ruyter’s unsteady tracing retains the primary effect of photography as it generates a secondary, labor-intensive inscription of hand drawing. In this sense the final image layers distinct, if partially submerged, prerogatives of still photography, cinema, drawing, and painting. The aura of each ghostly medium, haunted by a specter of earlier or later processual incarnations, whispers hints of its own indelible temporality, its own image technology, through the chambers of her work. From this angle, and perhaps only from this angle, Ruyter’s new paintings recall the complex materiality of Warhol’s serial silkscreens.

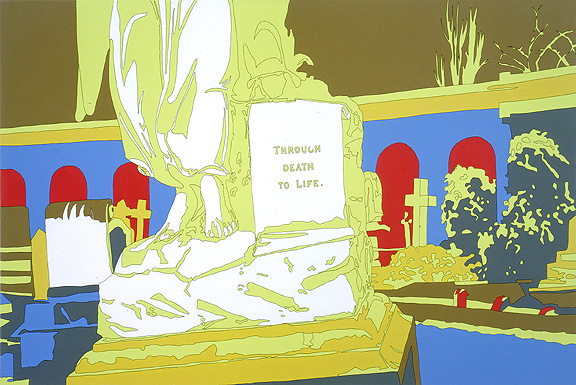

Encrypting frames of time, even units as elementary as ‘old’ and ‘recent,’ within a integrally recognizable motif – our belief that the depicted scenes really existed – inevitably raises the problem of narrative. Indeed the impression that Ruyter’s pictures harbor pregnant but concealed dramas is abetted by their pulpy titles and, in several new pieces, by squibs of language: “Two Cowboys Drowned”; “Through Death to Life.” To be sure, titles such as “Gardens of Stone,” “The Strange Door,” and “The End” are far from arbitrary yet turning them into skeleton keys that might unlock a narrative secret is a futile exercise (as nonsensical as describing Ruyter’s palette as ‘toxic’ or ‘acidic,’ the blunt instrument of an outraged expressionism). More productive is to regard the play of language and image as another means of signifying absence or perhaps more accurately, an etiolated presence. A few titles will be familiar, evoking other scenes, other historical junctures, the vague movement of character and story across the scrim of memory. The painted scenes they annotate may in consequence bend slightly in mood or tone but titles do not infuse the work with dramatic meaning. No malign anecdote lurks just behind a facade and Ruyter never enlists our gaze in the service of ‘offscreen’ space. Similarly, although several paintings inherit the rough format of ‘establishing shots,’ long views of a setting as preparation for the start of action, their adamant stillness and refusal of tactile cues make expectations for narrative even more questionable.

Two issues remain unresolved. The first concerns the moral tone of the work, the fact that the majority of titles are sewn with dark inklings of fate or morbidity, a practice Ruyter has continued from earlier series which were less inflected by ‘Gothic’ themes of decay. How then should we characterize the attitude taken towards the paintings’ landscapes and human inhabitants? Is the universe she invokes redolent of an endless necropolis in which bodies, statuary, faces carved into vaults, inscriptions of language, and stone crosses form a seamless continuum of diminishing vitality? Or conversely, do abstracted signs of human, or broadly organic, presence offer visual templates whose vitality is displaced onto patterns of shape and color? At the end of the day, are her quotidian motifs the source of curdled fascination or affectionate stoicism?

A final trajectory must revisit narrative time as an extra-scenic secretion rather than as a property of images and their linguistic overlays. On one hand, there is the familiar allegory of how the work came into being, our necessary inferences about the creative process, the ‘action’ of transformation from Real to Imaginary. But beyond that lies a spectral route joining one painting with another in a succession of visited sites. We need not know that Ruyter’s originary photographs were gathered at Brompton Cemetery in London, Pere Lachaise in Paris, Boothill in Tombstone, and Hope Cemetery in Barre, Vermont in order to realize that the grave of pioneer film fantasist Georges Melies could not logically be adjacent to the cactus-infested burial ground of two cowboys. Thus in the movement from picture to picture we retrace a tourist’s progress across thematically linked locations separated by palpable geographic and cultural differences. It might not be a sightseeing trip we would undertake on our own volition but staged within the confines of an art gallery, it boasts the clamorous appeal of all impacted – dare I say ‘Proustian’ – mental voyages.

Paul Arthur